Jonathan is still a virgin at twenty-eight — or so he says. From the look of his underwear, I’m tempted to believe him. His blinding white jockey shorts are far too big, hiked up to his ribcage like an old man. We’ve been friends for a long time. I’m between relationships at the moment, and on impulse, really, I’ve gotten him stripped down this far, but now he’s balking. His underwear acts as a kind of psychological barrier, I guess. We’re on my couch having an intense heart-to-heart.

Part of the problem is this woman he’s in love with. Even though she’s been living as a lesbian for two years, he keeps hoping she’ll come to her senses and marry him. It’s true, they still go to Temple together every once in a while; he even cooked her a seder last year. He and I talk about religion all the time; I’m a curious Episcopalian and I ask him everything about Judaism. I have this wild notion of converting someday — but he says it’s difficult, and I believe him.

I’m interested in having sex tonight, though I’m not going to push him too hard. With hindsight, my own virginity was surrendered far too casually. My first lover was a lot older than I was, a lot more confident, and I just let him do it because he was so persistent. It’s not that I don’t recognize the attraction, the magnetic purity of someone like Jonathan. No worries about disease, and he’ll most likely fall in love with me. A flattering situation, sure, but also a burden — one I’m not sure I want to take on. Jonathan’s an appealing but complicated case.

“It’s not that I don’t find you attractive,” he says, reaching out to take my warm hand in his clammy one. The flickering candlelight throws his cheekbones into sharp relief, hoods his eyes and makes him look exotic, mysterious. I want to see him in a yarmulke and prayer shawl, those little leather boxes strapped to his head and arm. “You’re very attractive,” he adds.

I move my hand up and down his bare thigh, feeling the few downy hairs there rustle back and forth over his smooth skin. He’s a lawyer for an environmental-protection group, and he runs eight miles every other day. Compared to him, I feel like a moral slug: a vegetarian since high school, he’s never even driven an automobile. “So are you,” I say. I play with the little opening in his shorts with one finger, teasing him like I would my cat.

He closes his eyes, leans his head back against the wall and draws his breath in. “Please don’t,” he says, his voice a little strained, his Adam’s apple bobbing. I take my hand away like something bit it.

“I just can’t do this,” he says, opening his eyes wide and staring at me. “Not tonight. Not this way.”

“Okay,” I say, getting up off the couch. Why did he think I was taking his pants off? Intellectual curiosity? Science experiment? Bending, I pick up his shirt and jeans and shoes. “Here’s your clothes. There’s the door.”

He sits there, his face frozen in a squint-eyed wince that makes him look like a chastened dog. He reaches up to touch his forehead with a forefinger. “I’ll probably regret this in the morning,” he says.

“You probably will,” I say, tilting my head and smiling.

***

Over time, according to his rules, I discover Jonathan isn’t only virginal, but also an old-fashioned romantic. He doesn’t like to think of himself that way, however. A reformed atheist, he talks about “significance.” “I want everything to be perfect between us,” he says to me. We’re lying in bed together at this fancy bed-and-breakfast he’s brought me to for the weekend.

“Perfect?” I ask. “Perfect?” My stomach is so taut with lust you could bounce a five-pound slab of beef off it. “What does that mean to you?” He’s been lifting weights every day for the past few months, and from what I can feel of him tonight through his thin knit shirt, he’s big and carved-looking and hairless like a god.

“A serious commitment,” he says. He turns to look at me in the moonlight. His eyes glisten, and he strokes my hair. “That’s what I’m looking for, after the fiasco with Melissa.”

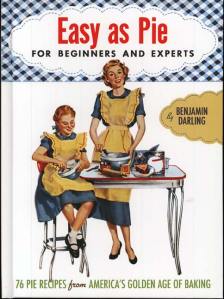

Melissa’s the lesbian he’s finally given up on. I don’t say anything at first. It all used to be so easy, so effortless. Everybody’s clothes came off as easy as pie. “God,” I say, the word arcing out of my throat like a wet watermelon seed. I lie there feeling my heart pound. He reaches over, tracing the lines of my eyebrows with one finger. “Give me strength,” I sigh.

Jonathan gets up on his elbow, his brilliant pectorals bulging, the mattress squeaking under him like a baby bird. “And what is so wrong with wanting to build a relationship first?” he asks.

“Jesus, you sound just like my mother,” I say.

***

After all this, I’m astonished when, a few weeks later, after dinner out and a cryptic Brazilian movie, he announces he’s ready for us to “move forward.” He leans down to kiss me, and I can tell he’s nervous. I’ve decided his full, red mouth is his best feature — on him it’s almost larger than life, contrasted with the rest of his austere person. He tells me his father’s mother was Native American, though when I ask him what tribe she belonged to he can’t say — but he does give me a real flint arrowhead to commemorate the evening. “I found this in a field out back of my parent’s house a long time ago,” he says. It’s small and gray and minutely chiseled, still warm from his hand.

“It’s beautiful,” I say.

We walk back to my apartment holding hands, hearing an odd blend of reggae and big-band music through the open windows of the neighborhood. In my bedroom, he turns quieter and quieter, seriouser and seriouser, as each piece of clothing comes off. As expected, I find him enthusiastic but unschooled. His hands are like roving mice, ticklish and prickly all at once. “Help me through this,” he says at one point, gazing up over my head at the O’Keefe poster in the far corner. Afterward, he doesn’t talk at all, just lies there with his arms crossed behind his neck. “I love you,” he says, groping for his glasses on the bed beside the table.

It’s like he punched me in the stomach with something soft. I turn over and put my face into the nape of his neck; he smells bland and sweet like oyster crackers. I don’t like it when men have a strong smell, but I don’t like it when they don’t, either. Hard to please. Or, maybe I want somebody who smells like me. Back in college, I developed a theory that the reason I never had a problem getting boys to like me was I emitted some sort of secret sex pheromone, more than other girls. It wasn’t anything about my personality that attracted men, but the way I smelled to their unconscious nose.

A more plausible explanation is that I was more unprincipled than most girls: I never broke up with a guy until I had a replacement waiting in the wings. I’d keep the old one around as a decoy until that happened, even if I was irritated beyond belief, even if his touch made my flesh crawl. Because, when you don’t have a boyfriend, the other guys think there must be a good reason, and stay away. If, instead, they believe they’re stealing you away from someone, they have an incentive.

But, right now, at least with Jonathan, I’m in a stage of trying to reform, change my ways. So, instead of saying “I love you, too,” which I know I could utter in a convincing enough voice, I hug him and sort of shiver all over, as if I’m so overcome with feeling it’s made me shy.

***

In due course, Jonathan brings over his toothbrush, clean shirts and underwear, and his second-best running shoes. He even arranges for Sunday newspaper home delivery, something I’ve always meant to get around to; however, as the weeks pass, I come to realize my period is overdue. I try to shrug it off at first, but after another week end up saucer-eyed and sweaty, marking off the days on my calendar over and over — consulting the lot numbers and expiration dates on the box of condoms and canister of foam we’ve used, as if they’re runes.

One night, soon after I start to worry, we go to this cowboy bar. I have authentic boots, a string tie, a silver belt buckle, everything but a neon sign saying “POSSIBLY PREGNANT.” I don’t say a word about my period, but all night he keeps staring at me as though he almost knows what’s up. I would like to be able to tell him, but I have a feeling he’s not going to make any of this easier. He’s not that kind.

He dances well, for a lawyer. “Why’d you go to law school, anyway?” I ask him, yelling over the music.

“I couldn’t face medical school!” he shouts, laughing, as we squeeze our way off the dance floor.

“I wanted to go to medical school,” I say.

“What kept you from going?” he asks.

“Math, I guess. I had this trigonometry teacher in high school who smirked every time I asked a question.”

“For me it was dissecting a cat,” he says, his face solemn. “I figured if I couldn’t handle that, there was no way I’d be able to do it with people.”

“Yeah, blood,” I say, with enthusiasm. “I tried to pierce my friend’s ears once. We used ice cubes. There was this teeny little drop of blood that came out when I put the needle through. One drop about the size of this mole,” I say, pointing to my own arm. He peers down. “I was instantly nauseated. But more terrible than the blood was the way her earlobe — my friend has really fat earlobes — the way her earlobe sizzled under the ice. Like it was meat frying or something. I didn’t think I’d be able to do the second one, but I had to — I couldn’t leave her with only one ear pierced.”

He nods, that awful, fake kind of nod people give you when you know they don’t have a clue what you’re talking about. “What an awful experience that must have been,” he says.

***

Early the following week, over at the clinic, I pee into a tiny paper cup with Bugs Bunny on it, and when the lab tech comes back into the room, she doesn’t say a word — she doesn’t have to, it’s there in her eyes, the set of her jaw. “Our first opening is next Wednesday,” she tells me, penciling something on a pink chart.

It’s probably racism or something, but on the scheduled Wednesday, as I lie there on the table trying not to shake, I’m relieved to see that the doctor who’s going to perform the abortion is black. As if somehow that makes it all okay — as if he’s a surrogate for guilt, for suffering. He seems nice, quiet and bookish, with big horn-rimmed glasses and a neat mustache. His voice is soft, vaguely Southern. I close my eyes and try to relax, but it’s impossible.

***

“Was it mine?” Jonathan asks a few days later, after searching my kitchen junk drawer for the 75-mile-radius map he loaned me, and finding instead the bright yellow booklet of follow-up instructions they gave out in the clinic’s recovery room.

I don’t even bother to ask why he thinks it might not have been his. “No,” I lie, and he stands there for several minutes, towering over me in the tiny kitchen, stiff and straight through his torso, his head and neck bobbing forward, nodding in place like a tired metronome.

***

“I don’t think we should see each other anymore,” Jonathan says later, sounding rehearsed, over the phone. I don’t like to do my dirty work in person, either, so I can’t complain about his choice of medium.

“Even if it had been mine, I wouldn’t have asked you to get married or anything,” he says. “I think you’re a very confused person.”

“Oh, really,” I say, trying to keep my voice neutral.

“You’re not in love with me, anyway, and you know it,” he adds. “You never were.”

“Get off your high horse,” I say, laughing. “You’re not in love with me, either.” I’m above reminding him of what he said on our first night together — it’s gone beyond such petty one-for-one recrimination to a whole new level, a swirling gray reach that makes me feel more tired than angry.

“No, but we should have been in love,” he says. “That’s my point. If the person I’m sleeping with gets pregnant, I want to be able to consider all the options, including marriage.” He sniffles into the phone, and I’m shocked to realize he’s been crying. “Obviously, I’ve never been faced with this before, but this whole situation made me stop and think. It’s too dangerous.” He pauses, and I can hear him breathing raggedly. “I made a mistake,” he says. “I’m sorry.”

For a minute all I want to do is hang up on him, smash the phone down like I’m smashing his face. It’s as if a more flippant attitude on his part would be easier for me to deal with, because — to a certain degree — I expected that.

“The person you’re sleeping with? People don’t get pregnant,” I say. “Women do.” He clears his throat, but says nothing, and then I know he’s only staying on the line out of politeness.

“Okay,” I say, after a few more moments of silence. “I agree. We shouldn’t see each other anymore.” I exhale, feeling each slow millimeter of my lungs’ deflation — the breathing not painful, yet, as it will be later, when I will have to use pillows to muffle the grief which will blow me to and fro, grief which I can no more harness or control than I could a demon, or a hurricane. I will be rattled, I will be shaken, I will be damaged.

“Goodbye, then,” he says.

“Goodbye,” I say, surprised by my voice’s new gentleness. Taking the phone away from my ear, I listen for the click and buzz and let it go, releasing the long, springy cord that I had stretched across the living room from the kitchen wall, the curved plastic form of the receiver skittering along the length of the coffee table like a live fish. And then I notice the strong afternoon light streaming in through the living room windows; how, despite its warmth, it makes the skin of my arms and hands look bleached, pale and waxy — almost like I’m already gone from this place.

I am happy to read it. Have a beautiful day 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderful. You are truly gifted.

LikeLike

wow, thank you!

LikeLike

You could definitely see your expertise within the work

you write. The world hopes for even more

passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to mention how they believe.

Always go after your heart.

LikeLike