Alabaster, Briefly

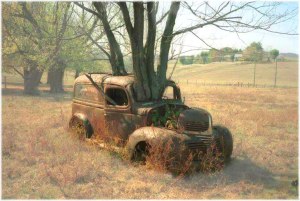

After the hurricane, but before the power came back on, Ella went out walking with her daughter, Katie, to survey the damage. The huge old ficus tree in front of the library had toppled over, its immense grove of roots lying naked, withering now in the sun. “Nana’s tree gots broken,” the three-year-old said. Humidity bore down on everything like a weighted fishing net. The tree had been a twig thirty-five years ago, when Ella was a kindergartner. She remembered the planting ceremony — her mother, president of Friends of the Library, in a blue linen sheath and white gloves, stepping on the edge of a shiny new shovel.

Now the tree, too, was dying. The shelter it had provided was still dark and cool — the web of roots from each branch created a division of rooms like a house. Ella pitied that sodden, gigantic mass, torn from the soil, not dead yet, but no hope, terminal. How long did it take a tree to die? Uprooted for half a day, the leaves were still supple and green. It would take days for them to wilt, weeks for a crew to cut the tree into logs and load the logs into a wood chipper. Her mother would be long-buried by then.

It was late August, and Sophia’s diagnosis had come in January, just after New Year’s. Ella was far away when it happened, stuck in New Jersey with a new job. Now her mother needed her and she was marooned. She had turned into one of those people she hated, one of the ones who moved away from their family to chase money, thoughtless and selfish, leaving their sick, their aged in the hands of underpaid nurses. “She’s in good hands,” Sophia’s friends told her over the phone, meaning the hospital.

Ella flew down after her mother’s surgery. The decision to operate and the actual sawing open of her mother’s skull had happened faster than Ella could get there. When she arrived, her mother was in the Surgical Intensive Care unit, bed number three. Sophia couldn’t talk yet. Her head was wrapped in a helmet of gauze, and over that, someone had placed a flowered disposable surgical cap. She looked like a confused scrubwoman.

Ella’s reaction when, at first, Sophia didn’t know her was not heroism but, rather, numb acquiescence, a slow nod to absolutes. Ella performed the worst sort of cowardice: cutting the lines free before it was over. In that first hour, Ella could feel the passage beginning, away from her mother — the slow casting off from love, the mournful horns, departing from a foggy land of illness. Her mother had a ruddy stubbornness Ella was shocked to see. Over Sophia’s lunch tray — each food sealed in a separate dish — her hands danced above a nonexistent teacup, squeezing a lemon primly into thin air. She had gone another way, in her soft hat, her skin hot, glossy as if with fever, the surface papery-soft but no longer familiar.

After that, Sophia’s pale and knowing return to her usual self was anticlimactic. Ella had expected to cry more, to feel something else, not this. Nothing was how Ella had imagined it, not Sophia’s furtive, over-the-shoulder glances of fear, not the way Ella’s stomach dropped as she stepped into the room, not the aching bones, not the past no longer claimed. Her mother seemed glued, as never before, to the newspaper and the television news shows. Finally, Sophia confessed to Ella how, for a couple of weeks after the operation, she had been under the brain-surgery-induced delusion that she’d murdered somebody, by stuffing them full of shoe trees, and had been waiting for it to be on the news, in the paper. How she’d kept waiting for the police to march in and cuff her, drag her off to jail. Sophia and Ella laughed, and the way the humor was mixed with horror was something entirely new to them both. Brain tumor jokes — a new genre, previously unexplored. How do you get a woman to stop shopping? Remove part of her brain.

The social worker at the hospital sent Ella out to look for nursing homes. In one of them, a man, or rather, a man’s body — with no visible, communicable cognitive function — was being fed through a gastric tube, through his abdomen. Ella took in the odor of urine, other bodily smells and functions. The man was an ideal nursing home patient, permanently hooked to his nourishment line like a freakish, prize-winning, squash. The nurses rolled him side to side in stages, every two hours, to prevent bedsores. He never opened his eyes or moaned. His family seldom, if ever, visited, the nurse said. Ella stood at his open door until the nurse drew her away. Ella wondered if she was seeing Sophia’s future. Is that what her mother’s life — everybody’s life — would boil down to? The specter of death winked at Ella through perfect cat’s eyes. What was past the curtain?

There are far worse things than dying young, dying suddenly. And so Ella said no to the nursing home. She calculated how much money her mother had and decided to spend it to make Sophia’s remaining life as comfortable as it could be, considering the fact that inside Sophia’s skull was a bomb, gathering energy to explode. Ella hired someone to nurse her mother twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. Someone with the right hands, the right smell. She interviewed them over the phone, scheduled in-person interviews.

Lillie had a gold tooth in front and wore outrageous wigs: red, blonde, honey chestnut. Her bosom was soft, like feather pillows. Ella knew Lillie was right for the job from the first second. How was that possible? All Lillie’s Bible-thumping was okay by Ella. She knew Sophia would be well cared for. She knew Lillie wouldn’t steal anything. She knew Lillie wasn’t, in any way, a spoiler.

Lillie believed in Hell. She described it one night, a pit filled with fire and snakes. Lillie’s eyes widened and Ella could see the white all around the dark iris, merged with the pupil in fear. Lillie believed in speaking in tongues, in visions, but she hadn’t made the commitment to become a Christian because, she confessed, she knew she wasn’t strong enough yet to keep all the Commandments. Lillie had borne a six-year-old son, father unmentioned, who lived back home with family. He was her shame but also her delight. She named him Christophe and had him baptized the same day he was born. She might not be saved, but her son was.

She was from Jamaica and already spoke in two tongues — one, a lilting version of Standard English, the other, a speedy patois she used to converse with family and friends. Ella wondered if Lillie had secrets — when Lillie spoke like that, Ella tried but couldn’t understand. She had inklings she, herself, was being talked about.

Lillie was good to Sophia and Katie. Katie loved to snuggle with Lillie in her bed, rolling against her enormous bosom, watching cartoons. Katie sought out Lillie’s bed even when Lillie was not in it. Lillie cooked chicken and rice dishes with a lot of saffron. Her hair oils and hygiene products covered the bathroom counter and the windowsill in the shower. She had feminine cleansing wash, feminine cleansing wipes, feminine deodorant spray and coconut-scented douche. Ella wondered what Lillie was trying to wash away with all that stuff.

Ella and Lillie met frequently in the night, checking on Sophia. Ella usually slept in a T-shirt, Lillie in a long, shiny pastel gown with lace about the neck. She glided softly on her plump bare feet and suffered from insomnia. When Ella couldn’t sleep, she’d listen at Lillie’s door and if the television was on, she’d knock. Together, they passed hours watching twenty-year-old British slapstick on PBS. Lillie never laughed, but most of the time Ella couldn’t stop until she suddenly remembered why the two of them were there.

You never know enough about a particular cancer until after the patient, in this case, your mother, is dying, Ella thought. Then you know, you get the whole picture. Then you’re suddenly an expert on the ugliness of the tumor’s tentacles laying waste to the brain, pushing aside healthy cells, strangling them in the search for nutrients, a vigorous weed nothing can kill. Healthier than normal brain tissue, hardy as a kudzu vine. The operation had removed a clump from inside Sophia’s head — mixed normal brain and cancer. What part of Sophia’s personality had been stored in those cells, then disposed of and lost to the hospital’s furnace? These neurons and those neurons, together, perhaps held the memory of Ella’s birth — Sophia couldn’t remember what she couldn’t remember. Ella didn’t want to know for sure what was gone.

An area of brain, diseased, removed, yet the surgeon explained how the microscopic roots fanned out — to remove Sophia’s entire tumor would be to remove her entire brain. The surgery would provide some extra time on earth, a substantial number of better days, but would not stave the weed off for long. Eight months almost to the day. The radiation treatments barely slowed the growth. The terrible vitality of the cancer equaled the slow deflation of Sophia’s life. Ella was useless to help in that regard, but took care of all the practical details, made it possible for Sophia to die in her own room, her own bed, on her own sheets and pillows.

Time moved forward but memory moved in many directions. Sophia’s oncologist said, “The cancer appears to be in remission.” Ella, an intelligent woman, a scientific woman, found herself pleading for divine intervention, for the laser beam of God to drill into Sophia’s head and burn out the tumor. Appearances of remission, external, controlled for a time. Sophia walked, talked, and played bridge again. But for eight months lived in the shadow of death. Ella was buoyed by the mercy of not knowing; crushed by the agony of not knowing. Sophia lived on the edge of the river, where each tussock of cool grass might be the last.

Sophia became confused, just as she had before they opened her head. She started taking pain pills for the growing headaches. “I don’t know if they think they’re fooling me,” Sophia said.

Ella caught her mother looking through her 19th-century medical dictionary, the same one Ella had pored over as a child, staring endlessly at the pictures of congenital birth defects. Hydrocephalus, and the like. You never know what cancer will do until it’s already done it, Ella thought. She wanted to transcend her awkwardness in speaking to her mother about her own death, but wasn’t able to. She held her breath until she felt faint, but no words came to her. Sophia knew she was dying; Ella pretended she, herself, didn’t. It felt like Sophia knew Ella was merely pretending, and spared her anyway, one last act of maternal grace. Apparently, Ella was good for only the simplest things, things like comforting her mother with voice and touch as she became more and more childlike.

But really, Ella wasn’t good even for that. One afternoon when Sophia was knocked flat with pain, Ella tried to lie down in bed with her, stroke her back, the way her mother had done for her all her life. “No, don’t, it hurts,” Sophia said.

Ella, feeling helpless anywhere but at her mother’s side, stared for hours at old photographs. In one was the three-year-old Sophia, sitting on her father’s knee, dressed in white, a huge bow on the top of her head, a mass of dark curls, her small legs unexpectedly spindly, her feet surprisingly bare. The sole of her foot held the whorls of this day, this moment. Ella tried but couldn’t decipher the expression in her grandfather’s eyes. What would he say, that circumspect ghost? How to explain to him, how to excuse the futility of all Ella’s lavish preparations?

That night, Ella dreamed Sophia gave her old Bible to Lillie instead of her. And in the dream Ella was terribly hurt by that, but since her mother was dying, tried not to show it, and wondered, with the agony of a child, why her mother hated her so much. Lillie’s eyes, round and widened, with either alarm or fear, darted hawk-like around each room, and those eyes, surrounded by her smooth features and her gleaming, dark-brown skin, those quick eyes seemed to hold all feelings, all knowledge.

It was Lillie, Ella had to admit, who did the most work for Sophia. In the days that followed, Ella could only watch as the bond between the two became stronger. The next week, Ella was back in New Jersey, resigning from her job and packing the contents of her office.

“Take as much time as you need,” her boss said kindly, but she knew he didn’t really mean it.

“I need more time than you can possibly imagine,” she said, and he nodded and tried to look sad.

On the phone later that morning, Lillie told Ella how Sophia seemed so much more cheerful since Ella had departed. “She’s perked up so much,” Lillie said. Ella wasn’t surprised.

Back in Florida for good, Ella grew angrier by the day. She lay awake nights fuming about the receptionists in the oncologist’s office who made her feel like an obnoxious pest for calling. Their crisp, girlish voices made plain there was nothing more they could do other than prescribe painkillers. Why didn’t Ella realize that and leave them alone? Then she chided herself for being enraged by their callousness. Rational thought had vanished. Ella’s remaining thoughts and feelings flew around like feathers and fur and sometimes, like lazy dust balls.

Katie, at bedtime: “I’m scared of monsters. A tiger is in here.” When asked to cease and desist: “I’m just being quiet. Don’t talk, Mommy.” Ella watched her breathe after she fell asleep — both her daughter and her mother were flying along far, far above her, and she couldn’t seem to rise.

The day before the hurricane Sophia said, “Hi, sweetie,” and smiled when she saw Ella. Sophia was close to dying but Ella felt her mother still knew her. Sophia held Ella’s hand and kissed it. She rubbed Ella’s arm. Her mother’s head, as Ella adjusted it on the pillow, felt so warm, so heavy, and so sweet. Her hair — smoothed flat behind her ears. Her nails painted red by Lillie, she lay on pink embroidered sheets, sporting pale shamrocks on her homely nightdress. The steel bed-rail gleamed, chilling against Ella’s thighs as she leaned in to try to glean some intricate, fine-grained meaning from the hour. The charging ceramic horse she had hung over her mother’s bed, the one which had driven bad dreams away in childhood, his mane still wild and golden against the gloom, would be only a minor talisman in the end.

A urine catheter and bag hung on the hospital bed’s side-rail. “Is that juice?” Katie asked the first time she saw it, and Sophia and Ella both laughed. The tubes were transparent at first, then, growing clouded and organic with use, became less a fixture than anything.

It was too hard for Ella to bear. Every time she went in the room her mother grabbed her hand, gripping with all her strength. The way she looked at Ella — she wanted to tell her something, but what? Ella wished she could stay away. She wished it wasn’t like this. She wished they could just sit in the living room together, watching TV and Sophia could needlepoint.

Ella waited for the hurricane. Last week had been her mother’s birthday — the storm would be her penultimate gift. But Ella didn’t know that until afterward. Memory back-filtered such telling details — pictures of the dying mother were snapped, then parts of the view faded but parts brightened. Life as journey, as vision, as caress. Each thing became smaller at first, then loomed larger. Her mother’s eyes, teeth, hair. Perception was flawed. The hopeless interpretation of the mind. Where was her guardian angel?

Suddenly, Ella was in love with hurricanes as never before — yes, there was the threat of death, nothing new, especially these days, but there was also the stupefying power of the wind, the pelting rain. Ella longed to be in awe, in supplication, flattened, watching the storm roll over her body like a man would, naked, trembling with powerful need of her, shouting with passion as she lay under him. She was overwhelmed by the feeling that this was the way things needed to be. For so long, a storm had been raging inside her — it was a relief to have it visible, a relief to simply be reduced to holding on.

In the past, when Ella’s mother wasn’t dying, she always drank to excess when a hurricane was approaching. Sophia had always seemed terrified by the darkening sky, the strengthening gusts of wind, and the first huge, cold, solitary raindrops that pelted heads at random. When hurricanes were on the horizon, she cooked elaborate cream sauces, and served lemon-and-honey tea shot with brandy in crystal cups. When a hurricane arrived, Sophia was always more or less unconscious.

But this time, Sophia wasn’t afraid at all, instead, comforting Katie from her deathbed — the three-year-old crawled in with her, not Ella, in the middle of the hurricane. Ella was too tired to have any more hurt feelings. “There, there, nothing’s wrong, baby,” Sophia crooned. Ella pretended it was herself in her mother’s grasp.

Sophia wasn’t afraid, and then Katie wasn’t, either. Sophia, in the middle of that hurricane night, showed Katie it was just the wind… showed her the trees, whispered into her ear, in the midst of baby curls. Ella knew how that felt, her mother’s velvet skin between the ear and the shoulder, all of it perfumed silk. Ella closed her eyes and slept.

Later that night, just before dawn, while the wind ravaged the trees and tugged on the roof of the house, Ella woke to hear Sophia speak for the last time, the sleeping Katie draped across her chest. “Ella, Ella,” her mother breathed over and over, quietly, so as not to wake the child she held. “Ella, Ella.” Sophia smoothed hair she believed was Ella’s as she whispered. Ella watched from her mattress on the floor, afraid to move.

Sophia’s death waited while the wind roared, her death staring with great golden leopard eyes, unblinking. The mercy of the teeth sunk into the throat. To stay, to leave — it became the tiniest of steps. The tears in her eyes. The death dance, the death rattle. The odd, rhythmic, hitching respiration, the sticky sweat, the clock wound up by Sophia’s parents’ lovemaking finally unwound. Sophia died late on the morning after the hurricane. Ella was there, holding Sophia, as she drew her final breath. And then exhaled. Tick-tock — then nothing.

In truth, she lost track of her mother’s breathing as it stuttered and missed — her own heartbeat seeming to slow down — had that really been the last, the last? Waiting for the next inhalation, straining to hear. Ella just missed it, missed it. Then it dawned on her, too late, Sophia wasn’t breathing any more. Or was she?

“I think I saw her chest move,” Lillie said, panting hard. She ran to Sophia’s dresser and grabbed a mirror, holding it in over Sophia’s face, peering for signs of breath. Lillie’s eyes were dazed, her hands trembling, humid, as she passed the mirror to Ella. At first Sophia’s hand felt the same as always, but in a few minutes her color had completely gone. Her skin was whiter than Ella had ever seen it. White, translucent, her dead mother became alabaster, briefly — a warm, heavy sculpture. The funeral home people didn’t let Ella watch her mother stiffen, cool. They hustled her out of the room, didn’t let the daughter see them zipping her mother’s body into a bag. Had they forgotten that zippers made noise?

Lillie hovered over Ella as if she were spun glass, falling toward the floor. Lillie’s hands were once again warm, strong and capable, but in the end had not been enough to keep Sophia alive. She stripped the rented hospital deathbed and sponged the plastic-covered mattress with lilac-scented disinfectant. Ella crept into the bathroom and locked the door, listening to the sounds outside with great weariness. She eyed the bathroom window, wondered if she could fit through.

The water Ella drank to wash down her first tranquilizer was terribly cold. On her tongue it was like an immaculate knife. When Ella told Katie that Sophia was up in heaven now, with God and the angels, Katie’s voice grew soft and sad: “I wanted her to stay the way she was.” Me, too, Ella thought. Me, too.

Ella stood in the driveway and watched the black hearse move off down the road. Lillie was soon engrossed in cooking — gigantic pots of black beans and yellow rice. The smells filled the house, harmonizing with the soapy lilac already there. Ella’s first post-hurricane, post-mother walk with Katie was a mixture of familiarity and revelation — she was used to seeing that kind of wreckage. She was prepared for the smell – the ocean things, dead and rotting washed-up things.

That night, Lillie snored through it all, her mouth hanging open, trusting, defenseless, still waiting to be strong enough to get saved. She had not heard Sophia’s last words, and for that Ella was glad. Ella, Ella, Sophia sang out in the night like a chant, the repetition of the name apparently bringing her ease when might otherwise have been terrified. Ella realized, as she had not before, how much she loved wind and rain, how much she loved how the world was made disheveled and clean by a hurricane. She clutched her daughter’s small, hot hand, wondering how the child would remember this day; remember her when it came to that. “Nana’s tree gots broken,” Katie said again. The child lifted her arms, asking to be held, and Ella obeyed. She buried her nose in the curve of Katie’s neck and breathed.